I was about a third of the way through Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside when I realized I was reading a fantasy novel about the future.

Not in any literal sense, so far as I know; this is a secondary-world fantasy, set in a vaguely Renaissance-ish city-state. But the magic system in Foundryside is technological. I don’t mean that in a reversal-of-Clarke’s law sort of way; magic in Foundryside can be ineffable and slippery. What I mean is that it interacts with its society in many of the same ways information technology interacts with our own.

One performs magic in the world of Foundryside by writing code, in a way: by inscribing sigils on objects to make those objects believe reality is slightly other than it is. Once a writer has established an economy based on the manipulation of code, both at the level of human communication and at the level of the structure of matter itself, he can follow the implications of that.

“If you want to know what a mouse is,” writes James Gleick in The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, “ask instead how you could build a mouse.” Even in our own universe, the distinction between substance and idea is an illusion, and the way both of them work is by code, by writing. In the beginning was the word. In the end is capitalism.

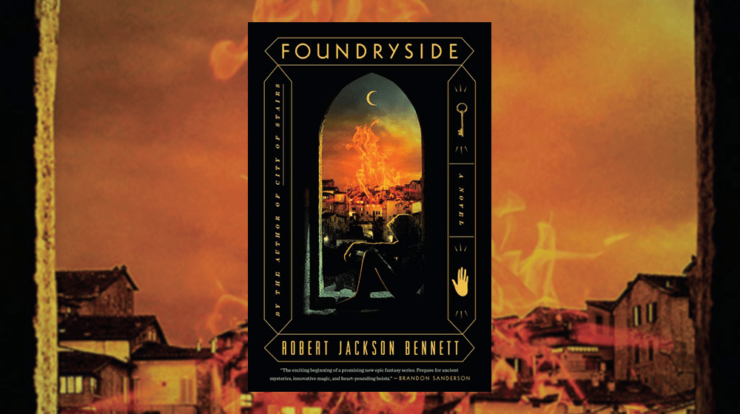

Buy the Book

Foundryside

Thus Foundryside is asking many of the same questions science fiction is asking these days, about how the information age is changing our reality at a social and even at a physical level. And because it’s secondary world fantasy, and not science fiction, it’s asking those questions with a different aesthetic tool kit. (At least one character could be considered a magical cyborg, which is something I don’t think I’ve ever seen before). Because magic in Foundryside is both an invented system and a numinous fact of the universe, it asks us to consider information with a similarly broad lens.

This is a fantasy book that is deeply, fundamentally about its own magic system in a way few fantasy novels are. Its characters don’t use magic so much as magic uses them. The medium of power determines its message, so the political question is not only who wields the power, but how it wields.

“Every innovation—technological, sociological, or otherwise—begins as a crusade, organizes itself into a practical business, and then, over time, degrades into common exploitation,” writes a character about two-thirds in. “This is simply the life cycle of how human ingenuity manifests in the material world. What goes forgotten, though, is that those who partake in this system undergo a similar transformation: people begin as comrades and fellow citizens, then become labor resources and assets, and then, as their utility shifts or degrades, transmute into liabilities, and thus must be appropriately managed.”

That’s a rare moment of overt political philosophy (carefully shunted to a chapter epigraph) in a book that isn’t didactic, and that stops short of being an allegory. It reads like a satisfying, gorgeously crafted fantasy heist starring a thief named Sancia, with plenty of gripping action scenes. And that’s what it is. But it’s also something else, something that made my eyes widen ever further as I read, as I started to get a sense of what Bennett is doing with this trilogy.

For a trilogy it is, and I’m excited to read the next installment, not only to see what Sancia and the other characters get up to, but also to see how the implications of the magic system unfold.

Kate Heartfield’s time-travel novellas, Alice Payne Arrives and its sequel Alice Payne Rides, are available from Tor.com Publishing. Her first novel, Armed in Her Fashion (ChiZine) is out now, as is her first interactive novel, The Road to Canterbury (Choice of Games). She is a former newspaper journalist who lives in Ottawa, Canada, and tweets at @kateheartfield.

Kate Heartfield’s time-travel novellas, Alice Payne Arrives and its sequel Alice Payne Rides, are available from Tor.com Publishing. Her first novel, Armed in Her Fashion (ChiZine) is out now, as is her first interactive novel, The Road to Canterbury (Choice of Games). She is a former newspaper journalist who lives in Ottawa, Canada, and tweets at @kateheartfield.

Sounds interesting, thanks.

It seems to me there’s no end to the magical cyborg examples out there, depending on how you define it. Peter Pettigrew’s silver hand, for example, could count as a simple example – that hand is a few steps beyond a prosthetic.

I feel like I’m missing some much better examples that are just eluding me right now, though…

Not a cyborg as such, but wouldn’t the golem qualify as a magical robot?

This selling Foundryside short. Foundryside is a reimagining of the cyberpunk genre in a fantasy setting. Cyberpunk is a dated and increasingly irrelevant genre and innovations like this arereally the only way to keep it alive.

Foundryside is simply awesome. Layers and layers and layers.

Magical cyborg examples:

Corum Jhaelen Irsei has body part replacement.

Alphonse Elric has full body replacement.

If you mean a human head attached to an inorganic body… dunno.

Thank you for this, can’t wait to get my hands on a copy of Foundryside, need something to balance The Expanse.

By the way, magical cyborgs, how about Fullmetal Alchemist?

Agree that Foundryside is awesome and the magic system is just one aspect that makes it so compelling. The main character being a woman of color with special powers and a problematic, murderous past and a primary companion which happens to be a magical key is another great reason. And I haven’t even mentioned the mysterious (and relevant) history of the god-like Founders which permeates the story’s setting.

These comments will be inundated with examples of magical cyborgs, I bet. The ones I thought of were from Baum and Mieville.

I really like Bennett’s books. I’m reading City of Miracles and look forward to reading Foundryside.

Was coming here to make the Golem comment as well, so it’s a pretty old concept. Recycled many times, most enjoyably for me in Lois McMaster Bujold’s The Spirit Ring.

It’s been a while since I played the game, but this thing about sigils reminds me of the magic tech in Dishonored. Anyone else?